Teatro Regio

Originally called the New Ducal Theatre, the Teatro Regio in Parma was built at the behest of the Duchess Maria Luigia of Habsburg-Lorraine, wife of Napoleon, who was sent to govern the Duchy of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla following the Congress of Vienna. Work began in 1821 on a project by the court architect Nicola Bettoli and the Theatre opened on 16thMay 1829 with Zaira by Vincenzo Bellini with a libretto by Felice Romani.

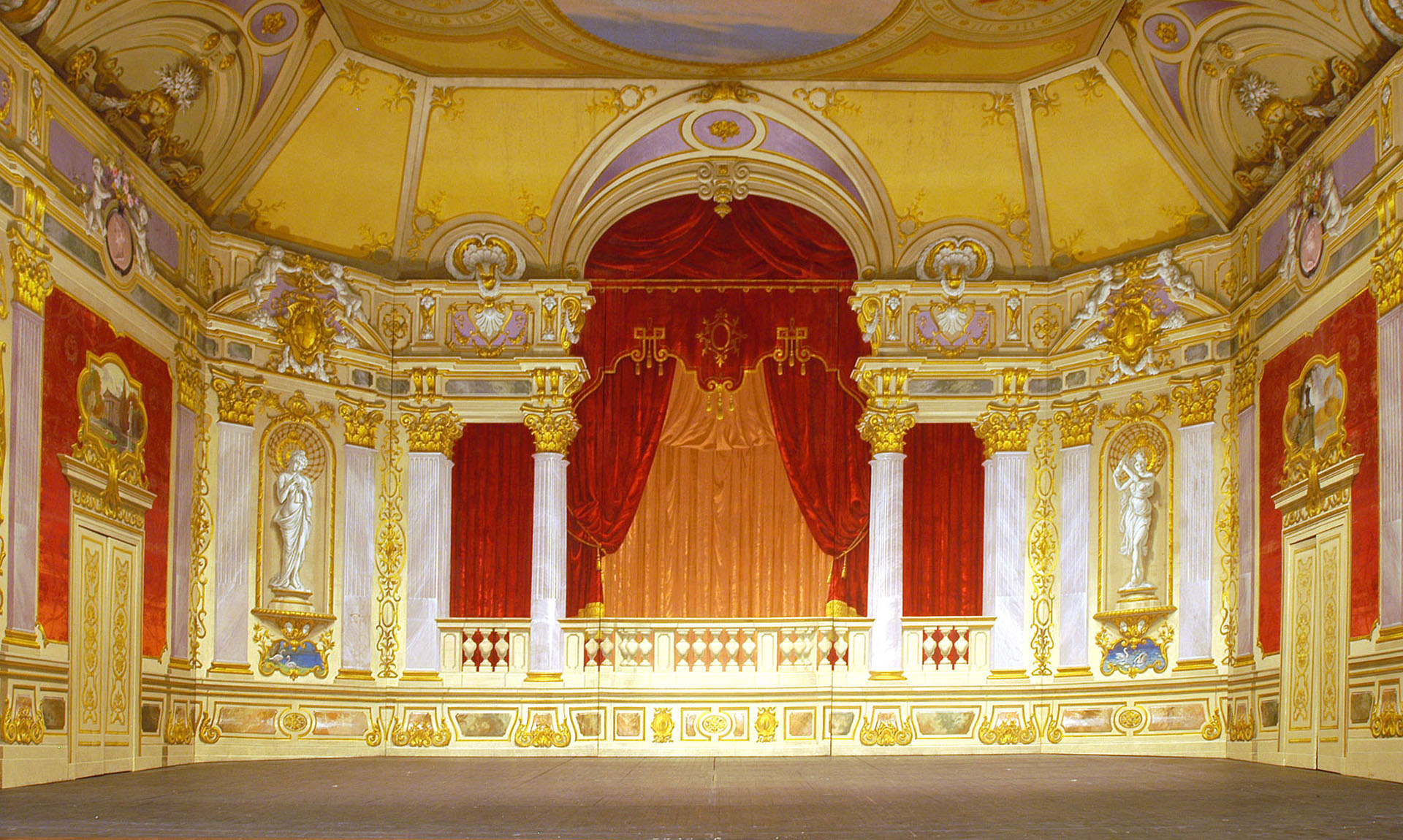

Built in the neo-classical style, the façade is characterized by a colonnade with ionic capitals with a large thermal window above. Having entered the theatre, we accede to the Foyer adorned with two rows of four columns and still visible on the floor the grills once used for heating the theatre. A staircase leads up to the large salon called the ‘ridotta’, where Maria Luigia’s throne was situated. The Duchess had direct access to this salon from the Ducal Palace. Two large blown glass chandeliers hang from the ceiling and the tribunes for the dance orchestra overlook the large space. Returning to the foyer, entrance to the main body of the theatre is through the door of honour: the stalls area, four orders of boxes and the gallery and the ceiling painted by Giovan Battista Borghesi with poets and dramatists painted in a circle around the great “astrolamp”. This lamp in gilded bronze was ordered from the workshop of Lacarrière in Paris. The theatre curtain is also the work of Borghesi and is one of the very few to have survived to the modern day; it depicts an allegory of wisdom with Minerva enthroned surrounded by Gods, nymphs, poets and muses. Minerva is a portrait of Maria Luigia herself. Above the curtain is the special clock ‘a luce’ which tells the time in five minute intervals; it is in the centre of the proscenium arch and on either side of the arch can be seen gilded busts of poets and composers. As we see it today the Theatre is very different from the original; in 1853 the neoclassical décor designed by Paolo Toschi was covered with the gilding and stucco work of Girolamo Magnani who had renovated the newly named Teatro Regio at the behest of Carlo III Bourbon using the new-renaissance style. Magnani was the set designer preferred by Verdi and they often worked together. That same year the new chandelier inaugurated the arrival of gas lighting in the theatre replacing the previous system of candles and oil lamps. Electrical illumination arrived in 1890 and the chandelier was cut down in 1913 to improve visibility from the gallery. The acoustic chamber painted by Giuseppe Carmignani, another rare survivor from past times, repeats the decoration of the boxes and consists of wood framed canvas panels, which can be opened and closed telescopically to function with orchestras of different sizes and formations.

Originally the Theatre was destined for various types of spectacle, from opera to dance, from poetic declamation to the most diverse art forms; funambulism, gymnastics, acts with animals, scientific demonstrations, illusionism and displays of ‘curiosities’. Right from its inauguration, the Theatre has born witness and been a protagonist of the crucial changes which affected melodrama during the XIX and XX centuries, from the end of the period of Rossini to the triumph of the Verdi repertoire, to appreciation of the French and German experience, to the extreme evolution in terms of realism of Italian opera with Mascagni, Leoncavallo and Puccini.

Borghesi’s Theatre Curtain

This work by Giovan Battista Borghesi (Parma 1790 – 1846) represents an allegorical scene divided into three parts. On the right is Maria Luigia painted as Minerva, enthroned with the symbols of her power, the plumed helmet, a cloak and the staff of power. At her feet is the owl, sacred to the Goddess and to the right a nymph looks at the shield lying on the ground, symbol of peace. Behind can be seen the allegories of Abundance, Justice and Peace. Nearby are Ercole and Dejanira while above them all in an uninterrupted circle are painted the hours, symbol of the eternity of time. Behind the Goddess human figures playing the lyre can be seen representing subjects of the Duchess who love music and song. To the left of the painting, the heights of Parnassus peopled by Gods and spirits. Apollo in the centre is playing the lyre and at his feet can be seen a lion soothed by the divine music. Further behind are the Graces and near the grove of trees the poets Pindar, Homer, Virgil, Ovid and Dante. To the left of Apollo three muses: Talia, representing comedy carrying a mask, Melpomene, muse of tragedy carrying a dagger and Euterpe muse of music carrying a lyre on her shoulder. Hidden behind a tree, menacing almost and holding his pipes is Marsia, defeated by Apollo in a musical competition. In the centre of the scene straining to be released by the muses is Pegasus, the winged horse born from the blood of Medusa, who with a mighty kick released wisdom and poetry from the rock; it is as though Pegasus is advancing towards the spectators bearing anew his gift to humanity.

The painter

Giovan Battista Borghesi (Parma 1790 – 1846) studied in Parma at the school of Biagio Martini. In about 1815 he painted Homer explaining the Iliad and various rooms in the Ducal Palace of Colorno. He painted many works for the churches of Parma and the altarpiece for the Oratory of the Rossi in 1823 was rewarded with a Ducal subsidy which enabled him to go to Rome where, over the course of two years, he painted a number of sets for the Teatro Argentina. Returning to Parma he stopped in Perugia and Florence where, amongst other things and inspired by similar works by Raphael and Sustermans, he painted portraits of La Fornarina and Galileo. Having returned to Parma in 1830 he was nominated Professor of Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts. He restored the frescoes of Parmigianino in Fontanellato and then painted what are considered his masterpieces: the portrait of Maria Luigia which is today in the National Gallery in Parma, the ceiling and the curtain of the Teatro Regio, and the ceiling of the third room of the Palatine Library.

The acoustic chamber

Painted by Giuseppe Carmignani (1871-1943) the chamber is made up of differently shaped and sized panels for a total surface of 320 sq.m. The canvas panels are wood mounted and can be put together for different sized orchestra complexes. The painting reproduces elements of stucco and inlay used in the decoration of the boxes in the theatre and has been done with tempera using powdered colours bound with animal based glue. The painting has been carried out directly on to the canvas with no preparatory layer, which normally would have been done with chalk and animal glue, in order to preserve the lightweight nature of the panels.

The painter

Giuseppe Carmignani studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Parma with Gerolamo Magnani and Giuseppe Giacopelli. After working in the Teatro Regio in 1893 he worked with La Scala in Milan before transferring to Argentina where he created sets for all the State Theatres. In 1898 he was nominated teacher of perspective at the National Academy of Fine Arts and the following year of the decorative arts at the Buenos Aires University. In 1911 he returned to Parma and the following year took over the Chair of Decorative Arts at the Fine Arts Institute and later he became Director and teacher of scenography which has its seat in the attic of the Teatro Regio.

The light clock

Time found again, essay by Giuseppe Martini on the occasion of the restoration of the ancient watch by Paolo Valenti

It could happen at the end of a lengthy duet, when the tenor and soprano separate, hopeful yet aware of hostile and alarming circumstances; or else after the applause to a cavatina of exceptional bravura or even, why not, after a Shakesperian monologue or in the full fl ow of complex recitative. During the fi nal agony of the hero, better still the heroine – a Violetta, a Manon a Mimì – no, not there because we all know that there the die is cast. Well, maybe yes, just like when you wake from a dream? Don’t forget that it is also an unexpected moment for the public who a second before would not have believed what had just happened or that it could even possibly have happened, that a tiny and uncontrollable event could overcome and make headway through the darkness leaving in its wake a stageful of shadows crowding upon each other, make him forget what is all around and push him to a gesture both curious and unwary. That’s the moment comes when during a theatrical representation you feel the need to know what time it is. It is a situation both lightning quick and extremely slow, almost cosmic, making headway in an indefinite, dilated space, peopled with arcane sounds and distant lights. A time out of time which is measured from the suspended time on the stage, bounded by arias and choruses, by brandished swords and curses, to a fragment of existence bounded by the time of everyday life, which outside must be placed against bus timetables and the lowering of the curtain. It is at this point that the well behaved spectator, educated in the ways of the theatre and most especially by the ways of the Teatro Regio in Parma, turns to the clock above the stage architrave. Nothing dramatic, a quick look to check the numbers, discreet yet clear, which hove into view as though until that moment they had never existed. The well behaved and educated spectator knows how to read the astute combination of hours in Roman numerals and minutes in Arab numerals, the minutes which advance by fives and which together advise us of the passing of time discreetly, never obsessively. In fact, the clock in operation at the Regio Theatre has no hands just a well thought out system which displays one above the other the two providential numbers elegant and slim against a dark background, like something certainly not unforeseeable and incongruous in the city which welcomed Bodoni with open arms. The great Regio clock does not tell the time: it proclaims it in a stately whisper. Of course, people will then say that the presence of a clock in the theatre stems from other necessities. It is well known that when one looks at the clock it means that the show has arrived at a dead end, and it is not beyond the bounds of possibility that the Theatre planners thought in these terms as well as avoiding members of the public having to fiddle with their fob watches. It would also be good to think that the stage clock is yet another way in which the Theatre has specialized, as though to say that everything about the Theatre itself is directed at assisting and cocooning the spectator providing him with every single piece of information useful to ensure that his attention does not wander from what is happening on stage or, at the very least, in the red velvet theatre stalls. Without explicit documentation, a surname and a year incised on the framework have led us to the author of this ingenious project: Antonio Barozzi, surveyor and clockmaker born in Sissa in 1799, died in Parma in 1870, who perfected the clock already in 1828 a few months before the inauguration of the Theatre in May 1829 and who, on the 7th of May that same year was appointed official clock keeper to the Theatre with an annual recompense of 129 lire for doing what was laid down in article 151 of the Theatre rules and that is “the duty of putting up the stage clock every evening that the Theatre is in use, lighting the prescribed system of illumination and putting it up without lights when the Theatre is used for rehearsals”. The extremely simple mechanism is that of a pendulum clock. A number of weights proportional to the resistance of the cog-wheel transmit energy to the rotator system until it sets off the movement of the escapement wheel, governed by a hooked anchor which, in turn, makes the pendulum move and whose oscillation ensures constant frequency to the system. The most fascinating part, however, is the method by which the two rings which show the hours and the minutes is moved. They are two large black rings, one with the numbers of minutes and the one below, which is larger in diameter, with the hours both lined on the inside with a strip of white paper and with protruding cogs in the upper left part of each number. In this way, the numbers cut into the black ring3 are blocked only by the strip of paper, which means that the light placed at the centre of the lower ring can be modulated behind the number. A metal hand hooks on to a fork hanging from the top and rests on the cogs of the upper wheel. Through a system of ropes, the result of the forces in play allow the metal hand to retract every fi ve minutes, so that it separates from the fork and free itself from the pivot allowing the ring to move anticlockwise only to be blocked again at the next pivot so that the wheel stops at the new hour number. From the Theatre can be seen the small “jump” that the minute number makes as it stops; this is the rebound of the metal arm against the wheel cog. Once the minute wheel has finished its twelve trigger movements, the system unblocks a second gated arm which in turn moves the larger wheel below by one trigger movement thus marking the hours with a similar mechanism. The hiding place of this ingenious chronographic mechanism is both arcane and impervious at 16 metres off the ground: a small rectangular room whose most significant occupants are doubtless the large rings with the hours and minutes and the cable junctions which transmit movement, while hidden in the shadows is the small and elegantly simple rotary mechanism which feeds the entire system. A bare wooden table with a stool which probably was used to lay out the cables complete the scene of this “Collodian” recess. It is a small room but, not to put too fi ne a point on it, it also has a reputation as a love bower from the contemporary legend that Maria Luigia is said to have decreed that whoever managed to being a girl up here to be kissed would have her fall in love for ever. However, we cannot be sure that the names and dates scribbled on the walls are those of successful lovers. It goes without saying that the pleasure of glancing up at the clock from the Theatre is increased by the elegance of the ornamentation which gives it a personality, one of reassuring accomplice, silent yet understanding of the theatrical evening. Unfortunately, in the absence of clear iconographic documentation as to the appearance of the architrave over the stage in the 1829 Theatre project drawn up by Niccolò Bettoli, it is impossible to establish exactly what the ornamentation which underlined the presence of the clock in the first neo-classical design of the room would have been like. It is not difficult, however, to imagine that in a continuation of the elegant style of that design it would have been a sobre variation on the sequence of swirls and palm leaves which decorated the upper frieze under the ceiling vault. It was Girolamo Magnani and Pier Luigi Montacchini, appointed responsible for the ornamental refurbishment in 1853 – when the former New Ducal Theatre had already assumed the name of Teatro Regio – who would elevate the clock to elegant protagonist at the summit of the stage: they surrounded the oval frame with a threaded frieze and placed it within a regal gilded wooden scroll (vaguely reminiscent of the Bourbon lily) with curlicues on four sides from which emerge laterally two flowering branches. In this way the clock was transformed into the visual culmination of the stage and not simply an object of consultation. It does not go without saying that during the 40 years that Barozzi was the untouchable and sacrosanct keeper of the clock at the Regio responsible for the correct functioning of the mechanism, that he always carried out the again maintenance himself which may have led to certain ambitions being nurtured in the bosom of the temporary helpers. In 1839, it appeared necessary to install a clock inside the stage area for the use of actors and singers. A supremely practical, almost severe, gesture and the now dismantled clock, formerly placed above the door accessing the stage from the first row of boxes to the left, came from the old Ducal Theatre within the Palace of the Reserve. Only a dismembered piece of the ruined mechanism now remains. Quite naturally the former glorious Teatro Ducale, situated within the Palazzo della Riserva until 1829, had its own clock in the XVIII century. The former site of that Theatre is now the central Post Office. Obviously at that time the length of theatrical evenings, the constant illumination of the Theatre and the frantic social activity amongst and between the boxes during the course of such evenings obliged the Theatre to have a highly visible clock; in the new theatre with the increasing use of semi darkness for representations, the clock was discreetly lit from the back. It is not clear why Pietro Veroni (1790-1878) of Parma was appointed to clean and repair this old clock from the Ducal Theatre and place it in position in the stage area of the new Theatre. From 1824 to 1831 he had played the kettledrums in the orchestra of the Theatre in Reggio Emilia (but Veroni was from Parma). It is very probable that the meager salary he earned as a musician forced him into re-inventing himself as a clock man as well as keeping his place in the orchestra. In 1839 Veroni cashed in 70 lire, though he had asked for 80, for repairing and putting this clock inside the stage area but was turned down as official keeper of the clocks in the Theatre. In recompense, the following year he was put on the books as a hopeful to play the kettle drums in the Ducal Orchestra of Parma where he stayed until 1856 distinguishing himself for the invention of a method to tune the drums using only one screw. Certainly a man of ingenuity. This is worth mentioning because the lack of focus as to the identity of the builder of the stage clock, Barozzi, has led us for too long to suppose that the documents about the transport and adaptation of the old clock from the Ducale to the inside of the stage in the Regio referred to the clock above the stage, thus giving to Veroni accolades which were undeserved. Veroni instead had re-adapted the old clock from the Ducale to use within the stage area: made of iron mounted on a lucid quadrant with numbers: he certainly remade many parts of the clock and changed the mechanism from vertical to horizontal. It was obviously more for the use of the actors than the singers as there were many displays of various arts, magic and scientific marvels displays which crowded the stage in the Autumn season: there were also many gala and festive evenings when the stalls area was cleared of chairs (the current style of armchair was to be adopted much later) and transformed into a huge ballroom. Its function, however, was to spare any kind of inconvenient episode amongst the artists who were more or less ignorant of the passing of time that the public could check on from the body of the Theatre. This then was the fact: a similar yet less elegant and less ingenious clock told the time for those working behind the scenes whereas the clock above the stage placidly communicated with the public. However, there is a lack of clarity in the XIX century documents where the generic expression “stage clock” is cited in the payments to Veroni for maintenance of the clock within the stage area and the main one above the architrave of the stage itself. As far as the Theatre clock is concerned, and it is after all the subject of this paper, its history coincides from now on with the history of its maintenance and repair. In 1850 following a suggestion from the administrative commission of the Theatre to the President of Ducal finances, it would be the son of Pietro Veroni, Giuseppe (born on 2nd February 1817), to be nominated to take over from Barozzi, without compensation and with the job of winding the stage clock every day and substitute for Barozzi in case of illness, a role that he would cover for at least 20 years certainly repairing the clock in 1855 and 1863 and managing to accumulate a reasonable amount of money thanks to his work as keeper of the clocks. Again in 1889 we have news of repairs to the Roman numerals which had overheated from the back lighting system. Further repairs were carried out in the XX century, the last one in 1979. Recent history from the turn of the century tells us of a “tired” mechanism which led to collapse and subsequent blocking of the system for a number of years; sad years in which it seemed that the time communicated by the Theatre, from the body of the Theatre itself no longer covered the practical and emotional role for the spectator. Pocket technology advanced and the elegantly outlined numbers appeared as little more than a dusty relic from a world no longer operative, an instrument which could easily be done without. But now that the clock has come back into its own, we will once again be aware of the elegant utility of an instrument which not only tells the time, it isolates us from other possible times so brutally banal, the time of haste and traffic on the ring-road, the lengthy measure of time at work and the brief measure of the web, the time of lunch breaks and matches. Inside the Theatre, instead, the only real dimension is that of the spectacle itself where all other perceptions are annulled, or falsified or in any event destined to meet in the square of the stage, over which reigns in the shadows a clock of ancient wisdom, which ignores the spasmodic anguish of minute counting and accepts its task of telling a different story, ancient and immutable which reveals itself only to those who have the intuition to embrace the fact that time in the theatre is to be in the theatre.